At its core, a blockchain is a type of online ledger where transactions are recorded in "blocks" that are chained together, making it almost impossible to alter past records. Imagine a public library where every book (or block) holds a record of a transaction.

Public blockchains, like Bitcoin or Ethereum, are open for anyone to view. Even though the identities behind each transaction are hidden (using random string addresses instead of names), all the details — like amounts of cryptocurrency sent, where it came from, and where it’s going — are there for anyone to see. This transparency is both a strength and a weakness. While it keeps things honest, it also means that anyone with the right tools can look at these records and analyze them.

How Blockchain Analysis Works

So, how do investigators look at all this transaction data? Blockchain analysis uses special tools to examine the patterns in transactions. Even though addresses on a blockchain are not tied to real identities, there are ways to find out who’s behind an address.

The Power of Patterns: Address Clustering

To track someone’s activity on a blockchain, experts often group related addresses together using patterns in the transaction data. If several addresses consistently spend from the same set of inputs, or if a single wallet repeatedly signs transactions that create predictable “change” outputs, those addresses can be algorithmically linked into a single cluster that likely belongs to one actor. Analysts also use metadata such as IP addresses leaked by poorly configured wallets, reused identifiers, or consistent timing and amount patterns to strengthen these links. Over time, clustered addresses build a behavioral fingerprint: how funds move, the services used, and the rhythm of deposits and withdrawals.

One particularly powerful way addresses get tied to illegal markets is through transaction patterns that match a market’s known deposit or withdrawal behavior. Marketplaces typically have characteristic flows: many buyers deposit funds into a handful of marketplace-controlled addresses, funds may be aggregated into hot wallets, and withdrawals to vendors and payment processors follow predictable schedules. If analysts find an address cluster that consistently receives deposits matching those schedules and then forwards aggregated funds to a small set of exchange addresses or known market hot wallets, they can tag that cluster as associated with a particular market. Once a cluster is tagged, any other transactions to or from that cluster gain context — they are now linked to the market.

Time and Behavior: Tracking Activity Over Time

Another tool in blockchain analysis is time-series analysis, which looks at when transactions happen and how often they occur. For example, if a market is suddenly receiving a huge number of payments all at once, it could signal that something big is happening — like an illegal marketplace opening or shutting down.

By seeing when transactions occur (for example, a sudden spike of activity on one address), analysts can start to notice patterns and behaviors. Are there certain hours or days when someone is more active? Is there a sudden drop in activity? These trends help identify unusual or suspicious behavior.

Spotting Outliers and Suspicious Patterns

Statistical analysis helps blockchain analysts spot outliers — things that are strange compared to the normal patterns. For instance, if an address suddenly receives a huge amount of cryptocurrency that’s far beyond what it usually gets, that could be a red flag. Analysts use math and data analysis to highlight unusual transactions and make educated guesses about what might be happening.

They might also use machine learning, which involves training algorithms to detect patterns in vast amounts of data. With machine learning, investigators can identify even subtle behaviors that humans might miss, especially when the dataset is large and complex. These algorithms can adapt over time, getting better at recognizing suspicious activities or behaviors that deviate from the norm. As blockchain data grows, machine learning becomes an increasingly valuable tool for identifying hidden illegal activities.

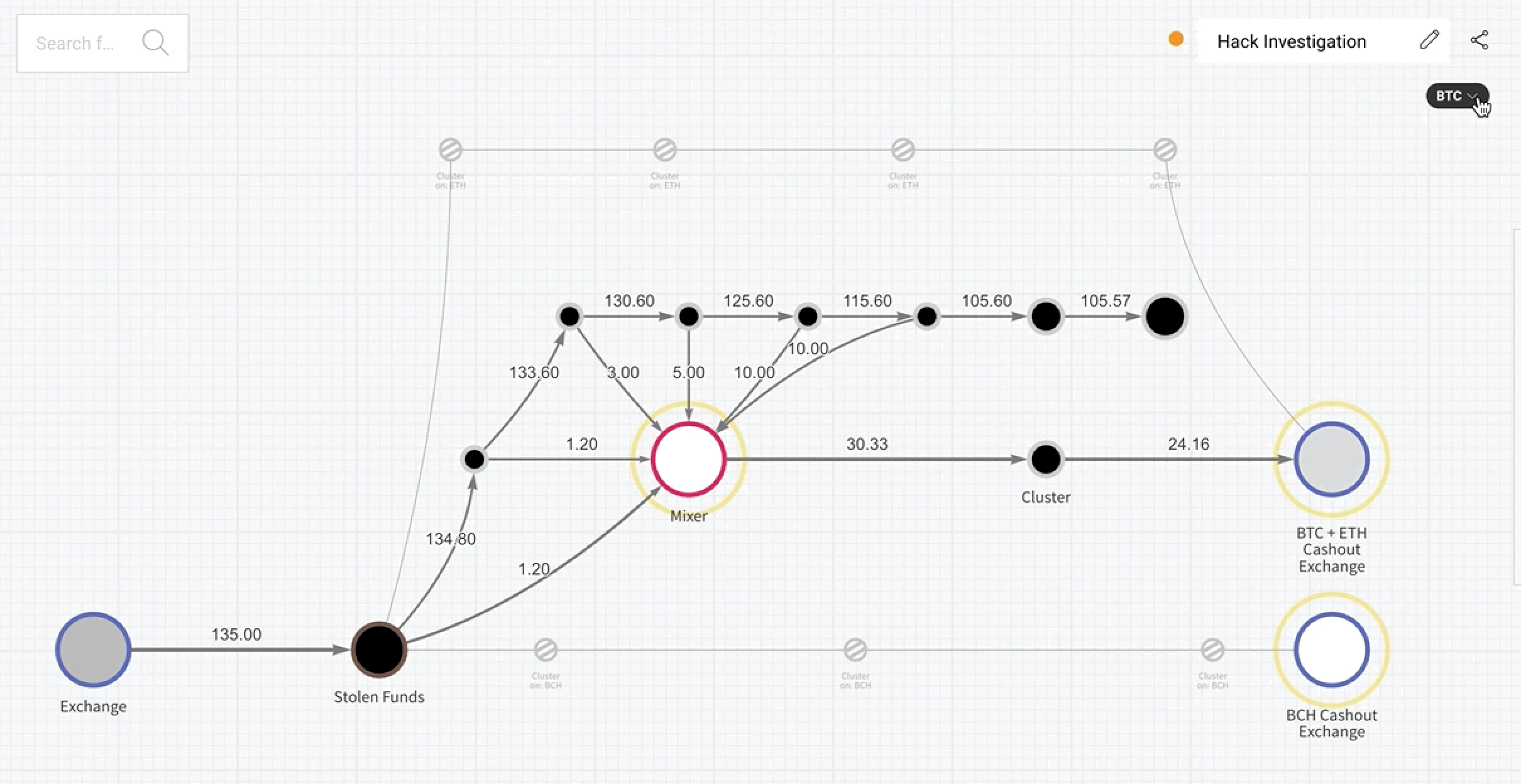

How Mixers Try to Hide Transactions

One way people try to hide their transactions on the blockchain is by using mixers. A mixer is like a "money blender" — it takes the cryptocurrency from multiple people, mixes it up, and sends it out to different addresses. The idea is to make it harder to track where the original money came from and where it’s going.

Mixers don’t make transactions completely untraceable, but they can add significant complexity to the process of tracking funds. While it's true that investigators can sometimes uncover the flow of funds, especially if a mixer gets seized or shut down, decentralized mixers can still pose a major challenge. It's not always easy to track who is using them because of the distributed nature of these services.

Despite this, law enforcement has had some success in uncovering mixer transactions, but this requires seizing internal records or finding other clues within the system. While mixers are effective at obscuring transactions, they do not guarantee complete anonymity.

How Law Enforcement Can Trace Privacy Coins

Despite the privacy features of coins like Monero and Zcash, law enforcement can still trace transactions through several methods. One of the primary vulnerabilities is at the onboarding stage—when users purchase or liquidate privacy coins on exchanges that enforce Know Your Customer (KYC) protocols. If a user buys Monero or Zcash on a KYC-compliant exchange, the exchange links the cryptocurrency to their real-world identity. Law enforcement can subpoena exchange records, creating a direct connection between a person and their privacy coin wallet addresses. Additionally, even with privacy features like ring signatures and shielded transactions, investigators can analyze transaction timing, volume patterns, and cross-chain movement to identify suspicious behavior and link transactions to known actors.

Beyond the blockchain itself, external metadata (such as IP addresses, server logs, or transaction errors) can also expose users. When privacy coins are used in conjunction with mixers or darknet marketplaces, law enforcement may seize internal records, exposing previously hidden links between on-chain pseudonyms and real identities. Furthermore, human errors—like address reuse or interactions with traceable assets—can offer investigators additional clues. Even the best privacy features are not foolproof; advanced blockchain analysis tools, along with pattern recognition and transaction flow analysis, enable authorities to connect the dots and uncover hidden illicit activities.

How Market Seizures Reveal Massive Data

When law enforcement seizes a marketplace—by taking servers, devices, or backups—it can unlock internal records (usernames, PGP keys, deposit/withdrawal ledgers, messaging logs, hot-wallet lists) that directly link pseudonymous on‑chain addresses to real identities. Those mappings let analysts retroactively tag addresses, connect previously separate clusters, and trace funds across time; even partial data (e.g., a few hot-wallet or payment-processor addresses) can exponentially expand an investigation. Seized records also let investigators cross‑validate on‑chain inferences (timing, aggregation patterns), turning tentative links into legally actionable evidence and often exposing users’ full transaction histories.

Why Mixers Are Risky if Seized

Mixers create a sense of privacy by design, but centralized mixers in particular are single points of failure. If authorities seize a centralized mixer and obtain internal logs that map incoming deposits to outgoing withdrawals, that operator-held linkage can deanonymize thousands or millions of transactions in one go. Even decentralized mixers and CoinJoin-style protocols can be risky depending on how they are used. The main risks are the same: any place where a real-world identity is recorded (an operator’s account, a KYC’ed deposit, a web server log) can create a bridge between on-chain pseudonyms and real people.

Beyond operator logs, mixer seizures can yield metadata such as IP addresses, email addresses, or payment records used to purchase entry to the service. Those off-chain traces are often the easiest way to convert an on-chain address into a legal identity. Additionally, when a mixer is taken offline, users who relied on it may rush to move funds, creating fresh patterns and mistakes (like address reuse or predictable withdrawal timing) that make them easier to trace. In short, mixers increase complexity but do not eliminate the danger that an external seizure or operational error will reveal the hidden mappings.

Exchanges, and Tracing Buyers

One of the most decisive ways blockchain transactions get tied back to real people is through on- and off-ramps — the services that convert fiat currency to crypto and vice versa. Most regulated exchanges and many over-the-counter (OTC) desks enforce Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) procedures. These processes require users to submit identity documents, proof of address, and sometimes biometric data. When a user buys cryptocurrency on such a platform and then sends coins to another address (for example, a marketplace deposit address), the exchange’s records create a direct, legally actionable link between the blockchain address and the purchaser’s identity.

Law enforcement can obtain that link by serving subpoenas or mutual legal assistance requests to exchanges, asking for account details tied to specific deposit or withdrawal addresses. If an exchange has a record showing that a KYC-verified user withdrew funds to an address later connected to illicit activity, that withdrawal becomes a crucial piece of evidence. Even when illicit actors try to avoid KYC exchanges by using peer-to-peer platforms, gift cards, or cash-based on-ramps, these channels often leave other traces — bank transfers, escrow intermediaries, or seller identities — that can be followed.

Buyers who think they are anonymous often slip up in small ways that defeat privacy: using the same exchange for both buying crypto and cashing out, reusing addresses, or sending amounts that match earlier deposit patterns. All of those mistakes make it possible for analysts to link a buyer’s KYC'd exchange account to subsequent on-chain behavior.

Analysis vs. Privacy Tools

When privacy coins, mixers, or chain-hopping are used properly, they can offer a high level of security and make transactions much harder to trace. Privacy coins like Monero and Zcash are specifically designed to hide transaction details, such as sender, receiver, and amount, using advanced features like ring signatures and shielded transactions. When used correctly, these coins can provide strong anonymity and make it very difficult for investigators to track or link transactions to real-world identities.

However, blockchain analysis can still sometimes find ways to work around these privacy tools. If a privacy coin user interacts with a regular exchange that enforces KYC, or if a mixer gets seized, investigators may be able to find links to the user’s transactions. Other techniques, like monitoring transaction timing or amounts, can also expose hidden flows. Moreover, even though privacy coins obscure most transaction details, they may still leave small traces or patterns, especially when combined with other activities like address reuse or chain hopping. Despite these challenges, investigators are using advanced techniques such as graph theory and entity resolution to connect the dots. Tools like cross-chain bridges, atomic swaps, and decentralized exchanges add complexity but can also introduce new monitoring points that leave traces for analysts to follow. It’s a dynamic "cat-and-mouse" game where both developers and investigators are continuously adapting.

Conclusion: Understanding the Risks

Blockchain analysis poses real privacy risks, but when used correctly, privacy tools like privacy coins, mixers, and chain-hopping can offer strong anonymity. However, even these can be compromised by centralized touchpoints (exchanges, bridges, payment services), seized servers or logs, operational mistakes (address reuse, predictable timing, reusing on‑ramps/off‑ramps), and cross-chain activity that leaves identifiable fingerprints. Advanced techniques—like graph analysis, entity resolution, and pattern recognition—can exploit even small correlations or partial datasets (e.g., hot‑wallet addresses, timestamps, or server logs) to link transactions and expand investigations retroactively. While privacy tools can be highly secure when used properly, they are not foolproof, and a single error or exposure can quickly unravel your privacy.

0 Comments